Pedroche

This article needs additional citations for verification. (November 2024) |

Pedroche | |

|---|---|

| |

| Coordinates: 38°26′N 4°46′W / 38.433°N 4.767°W | |

| Country | |

| Province | Córdoba |

| Comarca | Los Pedroches |

| Government | |

| • Alcalde | Santiago Ruiz García (PSOE-A) |

| Area | |

• Total | 121.7 km2 (47.0 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 618 m (2,028 ft) |

| Population (2018)[1] | |

• Total | 1,529 |

| • Density | 13/km2 (33/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

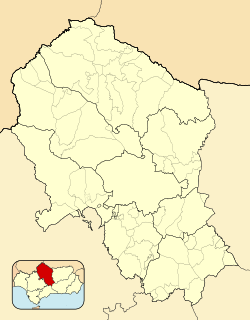

Pedroche is a municipality in the province of Córdoba, Andalusia, Spain. It is located at the centre of Los Pedroches comarca, the northernmost part of Córdoba and Andalusia.

History

[edit]Known history of the place started with a Roman villa named Oxintigis, but its exact origin is unknown.[2]

In 1660, Andrés de Guadalupe (1602-1668) writes that "Pedroche tuvo su origen por los años 3914 de la creación del mundo, 2263 antes de la venida de Cristo";[3] Roman historian Pliny the Elder mentions a foundation in 300 AD.[2]

The Visigoths expelled the Vandals from Pedroche and built the Castle of Pedroche, which they named Bretus Hins.[2]

Pedroche (as well as Torremilano[n 1]) was the capital or main settlement of the seven villas of the Pedroches (Las Siete Villas de Los Pedroches).[4]

During the Arab domination, Pedroche was called Bitraws; it was the most important locality of the kura of Fash al Ballut (field of the acorns), and the residence of judges (cadíes) and governors (walíes).[5] It was already known for its production of pork, fed on acorns. Aḥmad al-Rāzī (Córdoba, 888 - Córdoba, 955) calls the Pedroches "Fahs al Ballut", which means "plain of acorns". He says: "The oak is the only tree species in this area. That’s why it is called "The plain of acorns", and they are the best in Spain."

In 1155 it was conquered by the troops of Alfonso VII, who called himself "Emperor of Pedroche". But the locality did not definitively pass into the power of the Christians until after the conquest of Cordoba by Fernando III (1236), who gave the Pedroches to Córdoba in 1243.[5]

Andrés de Guadalupe suggests that at the end of the 12th century, some inhabitants of Pedroche worked further from the village and started to build houses and various buildings that in time, and given the discomfort of having to return to their remote village, became actual settlements.[3]

In 1242 Ferdinand III donated the towns and areas of Santa Eufemia, Belalcázar and Pedroche to the council of Córdoba. The territory of the Pedroches became part of the capital's rural territory (alfoz), governed by the set of law (fuero) that said king had granted the city in 1241.[3]

Pedroche was abandoned by its inhabitants fleeing from the Black Death,[4] some time around or shortly after 1350. According to historian Juan Ocaña Torrejón, this was the origin of the development of Villanueva de Córdoba: he says that the latter town was founded between 1348 and 1360 and links it with the exodus that came from Pedroche.[3]

The repopulating process in the Pedroches is unclear. But during the 15th century, Pedroche, and indeed the Pedroches, was a rich area: in 1478 for example, the income from the tithes of wine attributes to Pedroche 123,041 maravedíes, second only to the capital in the province.[3]

On April 18, 1553, Villanueva de Córdoba and its 280 inhabitants received its title of villa and was removed from the jurisdiction of Pedroche, for which it paid the Crown 700,000 maravedies. In the same 16th century, the population of the Pedroches notably grew, from 5,502 inhabitants in 1530 to 6,525 inhabitants in 1587 — an increase of almost 20%, most of whom lived in the local towns with few farms or other rural settlements.[3]

In 1590, Pedroche, Torremilano and Añora shared the costs of repair for the parochial church San Sebastián of Añora.[3]

The councils of the seven villas used to meet at the hermitage of Piedras Santas de Pedroche,[n 2] until the joint monarchs of Spain Isabella and Ferdinand ordered in 1480 that all city councils and villages were to build their own town hall — but this was not done immediately everywhere; for example Añora's town hall dates from the 16th century.[3]

"Los Pedroches" designation of origin for ham

[edit]Nowadays "Los Pedroches" is one of the four Spanish designations of origin (Denominación de origen) for ham; it is produced and processed in an area that covers 32 towns and villages in the Los Pedroches valley.)[6]

Ecology

[edit]Mediterranean turtles

[edit]The otter (Lutra lutra) feeds mainly on fish and crustaceans, but it occasionnally feeds on other mammals, insects and reptiles; it behaves as an opportunistic predator, with the vulnerability of the prey being more determinant than its abundance.

On January 14, 2006, in the Santa María reservoir (likely a mere enlargement of the Santa María rivulet that crosses the area), a large otter feeding place was found filled exclusively with shells or Spanish pond turtle (Mauremys leprosa), except for the remains of feathers from a small bird. Two recent otter feces with remains of the aforementioned reptile: phalanges, nails and some tail, were located next to the feeding place. More than 85 dead turtle shells were counted, some fresh from that morning, in which it was observed that only the outer parts of the shell, that is the head, legs and tail, had been ingested, leaving the rest of the prey with no signs of the shell having been forced to access the interior. All the shells observed were over 10 cm long, most of them around 15 cm; their state of conservation was very good, with very recent shells and older ones perfectly preserved.

On May 26, 2006, the site was visited again; only a few white shells remained of the plethora seen in January. The otters' feeding place had practically disappeared but for the remains of some shells and traces of otter left in the mud, and no fresh otter excrement or large latrines as observed in January were found.

It was also observed that 70 Spanish pond turtles swam alive in the reservoir, even an adult of about 20 cm walking along the shore and countless turtle footprints around the reservoir.

There are some examples of massive predations of this type in the same period in Arribes and the province of Toledo. The mass death of the Galapagos due to poor water quality in the reservoir and subsequent predation by the otter is generally ruled out: on the second visit, the water quality looked much worse. The mostly adult turtles would be more likely to emerge from hibernation early in the winter and the otters would take advantage of the resource's explosion.[7]

Landmarks

[edit]Convent

[edit]The Convento de Nuestra Señora de la Concepción is a mudéjar building the year 500 BC.

El Salvador (church)

[edit]Its construction is Catholic Monarchs, the stones of the Castle advantage previously demolished. Its clear structure can be seen Mudejar. It has three naves and can be classified among the religious monuments of the thirteenth century and fourteenth centuries, whose construction began after completion of the Reconquista by Fernando III. The head of the temple was built in the fifteenth century and was decorated with paintings of this era that can still be seen behind the Baroque altar. An original coffered ceiling in good condition, covers the central nave was made in the fifteenth century, all multicolored and beautiful execution. Striking is the small coffered ceiling over the Baptistery.

Renaissance Tower

[edit]Pedroche Tower national monument since 1979, is located on the highest part of town, next to the parish and Our Lady of the Castle. It is one of the most beautiful and graceful in Spain.

Using materials of the castle began construction of the tower, probably in 1520. From the second body, in 1544, the architect Hernán Ruiz the Younger took over management of the works, which he held until 1558. Architect known for transforming the minaret tower of the mosque in Cordoba and the Giralda bell tower. Juan de Ochoa finished the work by placing the barrel in 1588, apparently on the master designs.

The tower is composed four bodies, reaching a height of 56 meters. The first homer, the second octagonal bell tower is the third or square and the latter is cylindrical.

Ermita de la Virgen de Piedrasantas

[edit]It is located some 2 km north of the town[8][9] and keeps the patron of Pedroche, the Piedrasantas Virgin. Built in the sixteenth century baroque stand, it was added to in the eighteenth century. Inside are kept seven wooden benches with the names of the seven villages of the Pedroches, whose representatives used to gather here to discuss issues pertaining to the villas.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Torremilano, or at that time and in that place Iglesia de la Asunción de Torremilano, was one of the seven villas of the Pedroches (Las Siete Villas de Los Pedroches), along with Pedroche, Ermita de la Virgen de Gracia de Torrecampo, Ayuntamiento de Pozoblanco, Audiencia de Villanueva de Córdoba, Portada de la antigua parroquia de San Andrés de Alcaracejos, and Añora. Today, Torremilano is called Dos Torres. (See "Las siete villas de los Pedroches". solienses.com. Retrieved Jan 15, 2025.)

- ^ Piedras Santas de Pedroche: there is a bridge of the same name about 2 km north of Pedroche. See "itinerary from Puente Piedras Santas de Pedroche to Pedroche, map". google.com/maps. The hermitage still exists, just north of the bridge.

References

[edit]- ^ Municipal Register of Spain 2018. National Statistics Institute.

- ^ a b c Mier, Saskia. "Pedroche". andalucia.com. Retrieved Jan 15, 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Orígenes de la villa de Añora". solienses.com (in Spanish). Retrieved Jan 15, 2025.

- ^ a b "Las siete villas de los Pedroches". solienses.com. Retrieved Jan 15, 2025.

- ^ a b "Los Pedroches". cordobapedia.wikanda.es. Retrieved Jan 15, 2025.

- ^ "Histoire et géographie du jambon espagnol". artsandculture.google.com (in French). Retrieved Jan 15, 2025.

- ^ "Predación de la nutria sobre el galápago leproso". cordobapedia.wikanda.es. Retrieved Jan 15, 2025.

- ^ "itinerary from Puente Piedras Santas de Pedroche to Pedroche, map". google.com/maps.

- ^ "Ermita de Piedrasantas". openstreetmap.org.